Civil War Fife

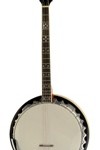

Civil War Banjo

Jew's Harp

Bealeton, Va. Drum corps, 93d New York Infantry

Throughout the Civil War, music played a significant part in soldiers’ daily lives. According to Aaron Sheehan-Dean in his work, The View From the Ground Experiences of Civil War Soldiers, songs persuaded men to enlist, comforted them during battle, entertained them in camp, supported them during drill and march, and reminded them of home (Sheehan-Dean 73). For both Union and Confederate soldiers, music provided an outlet to express their deepest fears and frustrations with the war. In addition, music also established necessary order and routine in the Civil War camps (Sheehan-Dean 74). The influence of these war time instruments and songs affected the soldiers living in 1861-1865, and even today the civil war music influences the way we as an American people celebrate our national pride and history.

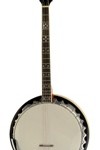

During the start of the Civil War, every regiment, which was made up of about 800-1200 men, was allowed to have a band of about sixteen musicians who were required to supply their own instruments. However, after the disastrous defeat of Union forces at the first battle of Bull Run, Congress decided that the Northern bands of musicians would only be allowed for the brigades which were made up of about 2,500-3,000 men (Rosengren 193). Two the widely recognized Union bands include the 7th New York Regimental Band and the 24th Massachusetts Regimental Band. Although marching brass bands were a newer concept during the time of the Civil War, both the North and the South believed these bands were essential to war. Confederate General Robert E. Lee recognized the importance of military bands and stated, “I cannot imagine war without Bands and music” (201). There were even times when the armies were not fighting that the Yankee and Rebel Bands would engage in a battle of the band music competition. In addition, many of the officers felt that the music played by the bands were important to maintain a high morale for the men (191). There were also more informal musical opportunities for the Civil War soldiers, and many soldiers brought along violins, banjos, guitars, spoons, and the Jew’s harp and played them for amusement during down time (Madden 88).

Many of the musical instruments were used to establish a schedule for a soldier’s day. David Madden in his book, Beyond the Battlefield the Ordinary Life and Extraordinary Times of the Civil War Soldiers reinforces this fact by including an excerpt from a Union soldier’s diary entry which states, “At five, the drummers and fifers, whilst the stars still shine, march around camp beating drums. Sleep is frightened from every eye; a stir, a bustle in every tent” (Madden 61). The fife and drum were common musical instruments used to establish order within army life. These instruments signaled the start of the soldiers’ day with the playing the morning Reveille, announced meal times, assembled the troops together, controlled marching exercises, and signaled lights out at night. Normally fifers and drummers were young boys between the ages of twelve to sixteen (Clark 31). As defined by the Columbia Electronic Encyclopedia, a fife is a small high pitched flute, normally wooden, that has six to eight finger holes. The fife was first used for military music in the late fifteenth century by Swiss regiments serving in France (Columbia Electronic Encyclopedia 1). Meanwhile, the drum is a percussion instrument that has a cylindrical or conical frame which is covered by a skin like material (Columbia Electronic Encyclopedia 1). During the Civil War, rope tension drums were most commonly used. These drum frames were made out of wood and the head of the drum were made from calfskin and tightly stretched with ropes (Madden 63). As the Civil War years continued, both the fife and the drum became more than just musical tools to establish order, but they also became symbols associated with American patriotism (Clark 31).

Another instrument used during the Civil War was the Jew’s harp. The name of this instrument is not derived from any relationship with Judaism. The Jew’s harp is a small ancient instrument made up of a metal frame that holds a flexible metal tongue. To produce sound the small metal frame is held between the teeth and the metal tongue is plucked to produce a note. Although there is only one tone that is heard when playing the Jew’s harp, there are different tongues which allow for additional tones (Columbia Electronic Encyclopedia 1). During the Civil War, these instruments were often seen during informal musical times in the camp (Madden 88). Another instrument associated with the Civil War is the banjo. This musical instrument derived from Africa and was brought over to the New World on board slave ships. Therefore, the early development of the banjo reflects the complex relationship between African Americans and Caucasians before the Civil War (Shaw 88). The traditional banjo is wooden and has a round-bottomed body that is hollowed out with dried animal skin stretched over the top of the body creating a chamber for echoes. There is also a longer wooden “neck” with strings that is attached to the hollow chamber. The number of strings on a banjo varies but, many contain one shorter string that is played as a drone (Shaw 84).

Since music was valued during the Civil War, the music publishing industry in the North and South was stimulated. There was more of an influence in the North because music business was more developed. Yet soldier on both sides aided the music publishing industry because many times the soldiers would carry around song books (Moseley 41). One soldier makes reference to the song books in his journal and writes, “We kept song books with us and passed much of our leisure time singing” (48). Popular songs among the Civil war soldiers included, “All Quiet along the Potomac” “Home, Sweet Home” “The Girl I left Behind”, “The Bonnie Blue Flag”, “The Battle Hymn of the Republic”, “My Old Kentucky Home”, “The Old Canteen”, and “The Union Right or Wrong” (Madden 89).

Although both the North and the South showed an appreciation for music and songs, the songs that stemmed from both sides were very different in patriotic message and tone. “Bonnie Blue Flag” was written by Harry McCarthy in 1861 and was the Southerners’ anthem. Meanwhile, the Northerners’ anthem was “Battle Cry of Freedom” written in 1862 by the composer George F. Root. In these song lyrics, the Union asserted their reason for fighting the war which was to preserve the national union. Meanwhile, the Confederates also stressed their reason of fighting, which was to fight for its rights (Mosely 48). Also, many of the Southern patriotic songs used lyrics filled with the notion of chivalry and feudalism. On the other hand, the Northerners made fun of the Southern songs by sarcastically mentioning chivalry (49). Through songs the North and the South lambasted each other. For example, Southern songs referenced their enemy and referred to them as Yankee despot, foul mudsills, bootblacks, vagabonds, and Northern scum (Sheehan-Dean 75).

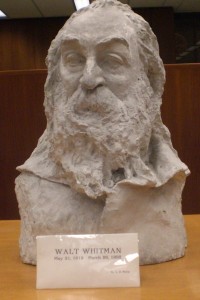

Since Walt Whitman was in Virginia and Washington D.C. at the height of the Civil War, he was able to witness the soldiers’ daily lives. Therefore, Whitman witnessed how music was used as a medium to express fears and frustrations of the War, glorify the nation, and for entertainment. In Whitman’s Drum Taps many references are given to the high esteem that music held for both the Northern and Southern armies. The title itself “Drum Taps” demonstrates the importance of music during the Civil War.

Work Cited

Clark, Jim. “The Fife and Drum In America.” Pan The Flute Magazine 27.4 (2008): 29-34. . Academic Search Complete. Univ. of Mary Washington Lib., Fredericksburg, VA. 18 October 2009 <http://web.ebscohost.com>.

Columbia Electronic Encyclopedia. “Drums and Fife, in music” 6.( 2009): 1: MasterFile Premier. Univ. of Mary Washington Lib., Fredericksburg, VA. 18 October 2009 <http://web.ebscohost.com>.

Madden, David. Beyond The Battlefield The Ordinary Life And Extraordinary Times Of The Civil War Soldiers. New York: Touchstone, 2000.

Moseley, Caroline. “Irrepressible conflict: Differences between Northern and Southern songs in the Civil War.” Journal of Popular Culture 25 (1991): 40-52. Academic Search Complete. Univ. of Mary Washington Lib., Fredericksburg, VA. 18 October 2009 <http://web.ebscohost.com>.

Rosengren, William. “Regimental Bands of the Civil War.” Journal of American and Comparative Cultures 24 (2001): 191-205. RILM. Univ. of Mary Washington Lib., Fredericksburg, VA. 18 October 2009 < http://web.ebscohost.com>.

Shaw, Robert and Szeed, Peter. “The Early Banjo.” Magazine Antiques. 164 (2003). 82-89. Academic Search Complete. Univ. of Mary Washington Lib., Fredericksburg, VA. 18 October 2009 <http://web.ebscohost.com>.

Sheehan-Dean, Aaron. The View From The Ground experiences of Civil War Soldiers. Kentucky: The University Press of Kentucky, 2007.

Silber, Irwin. Songs Of The Civil War. New York: Columbia University Press: 1960.

Image Citation

“Civil War Fife” Civil War Academy. Web. 20 October 2009

The Library of Congress. “Bealeton, Va. Drum corps” Web. October 2009.

“Banjo” About Banjos. Web. 20 October 2009